Introduction

The urine reducing substances (URS) test using Benedict’s reagent is a classic semi-quantitative screening tool used to detect the presence of reducing sugars in urine. This simple bedside test can offer crucial clinical clues in diagnosing inborn errors of metabolism, particularly those involving carbohydrate metabolism.

What Are We Detecting?

Benedict’s reagent reacts with reducing substances in urine. These substances have the chemical ability to donate electrons (i.e., they reduce other compounds). In this reaction, they reduce copper (II) sulfate in the reagent to copper (I) oxide, producing a visible color change.

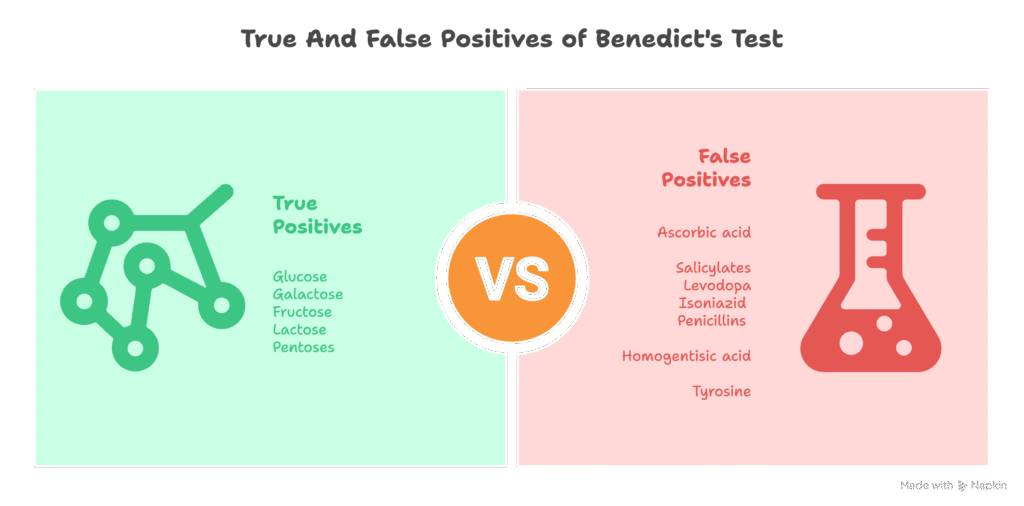

Common Reducing Substances in Urine:

- Sugars: Glucose, galactose, fructose, lactose, pentoses

- Other compounds (less specific): Ascorbic acid, cysteine, homogentisic acid, tyrosine, some drugs (e.g., penicillins), and ketone bodies

Chemical Basis of the Reaction

Benedict’s reagent contains:

- Copper(II) sulfate (CuSO₄) – the active component

- Sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) – provides an alkaline pH

- Sodium citrate prevents the precipitation of copper(II) ions (Cu²⁺) before the actual redox reaction takes place.

Under alkaline conditions and heat, sugars convert to enediol intermediates, which reduce blue Cu²⁺ (cupric) ions to Cu⁺ (cuprous) ions. The insoluble Cu⁺ forms a colored precipitate that ranges from green to brick red depending on the sugar concentration.

How to Perform the Test

- Collect a fresh urine sample.

- Add 5 mL of Benedict’s reagent to a test tube.

- Add 8–10 drops of urine to the reagent.

- Heat the mixture in a boiling water bath for 2–3 minutes.

- Observe the color change.

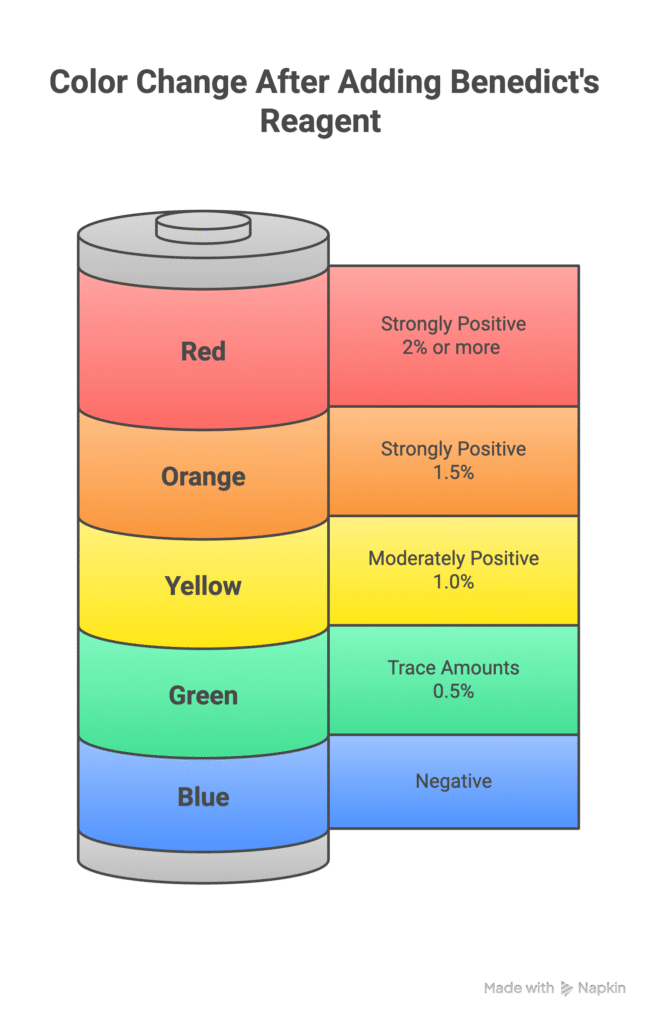

Interpretation of Results

The color of the solution indicates the approximate amount of reducing substances:

Important Tip:

Always perform a urine dipstick test for glucose on the same sample.

- If both dipstick and Benedict’s test are positive → glucose is the likely cause.

- If Benedict’s positive but dipstick negative → consider non-glucose reducing sugars like galactose or fructose.

When to Use This Test

Think of Benedict’s test in suspected metabolic liver diseases, especially in neonates and infants with:

- Hepatomegaly

- Jaundice

- Hypoglycemia

- Vomiting

- Poor feeding

Conditions where this test helps:

- Galactosemia: Reducing substance positive → start lactose-free feeds while awaiting GALT enzyme assay

- Hereditary Fructose Intolerance (HFI): Positive test → initiate fructose restriction after sending for genetic testing

If the clinical features are suggestive, the clinicians can start a lactose-free formula or restrict fructose in the diet based on the results of urine reducing substances.

- Tyrosinemia Type I: Metabolites like 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate can yield a positive URS result

Advantages

- Bedside test

- Inexpensive

- Easy to perform

- Useful early clue in metabolic diseases

Limitations

- Semi-quantitative

- False positives from:

- Certain medications (e.g., penicillin, isoniazid)

- Vitamin C (ascorbic acid)

- Some aminoacidopathies and organic acidemias

Conclusion

Though often considered outdated, Benedict’s test remains a valuable screening tool, particularly in low-resource settings or while awaiting confirmatory tests. A single color change in the test tube might be your first clue to a life-threatening but treatable metabolic disorder.

Disclaimer:

Genecommons uses AI tools to assist content preparation. Genecommons does not own the copyright for any images used on this website unless explicitly stated. All images are used for educational and informational purposes under fair use. If you are a copyright holder and want material removed, contact doctorsarath@outlook.com.

Join Our Google Group

Join our google group and never miss an update from Gene Commons.

Disclaimer: Genecommons uses AI tools to assist content preparation. Genecommons does not own the copyright for any images used on this website unless explicitly stated. All images are used for educational and informational purposes under fair use. If you are a copyright holder and want material removed, contact doctorsarath@outlook.com.

No responses yet